“Everything begins in Sakai,” a city where various histories and cultures are said to have originated. Senko incense sticks and wazarashi chusen, hand-dyed bleached cotton, are two of Sakai’s proudest industries that developed their own unique methods right here in the city of Sakai and are thriving still today. These crafts that have been passed down through generations are a testament to the ambitions of artisans who were driven by their dedication to quality and the pursuit of efficient production methods.

Sakai’s Original Production Method

Incense has a temporary existence, reminding us that life is short while burning quietly in the corner of a room. Its aroma possesses refined modesty and sweetness, and just a whiff of the scent brings you the feeling of calm and serenity.

It is believed incense as we know it today was invented in Sakai during the 16th century. While the only incense in circulation abroad then was simply scented bamboo sticks, a new method was developed in Sakai to manufacture a product with deeper fragrance that lasted.

In a city that had become a center of trade, raw materials for making incense such as fragrant wood and herbs were easily obtained and, aided by the demand from the large number of temples that called Sakai home, the production of incense accelerated. By the time World War II began, Sakai had grown to be a major producer of incense, with some seventy incense manufacturers in the area.

When the city was burned down during the war, many incense makers relocated to Awajishima Island in the Seto Inland Sea and continued to carry on the tradition that has now been passed down through generations. Today, Awajishima is the top producer of incense in Japan.

In addition to its use for religious ceremonies at temples and individual homes, incense are used for aesthetic reasons.

Senko as the Art of Fragrance

Senko incense sticks are manufactured in seven steps:

① Mix the ingredients until it has a claylike texture

② Shape into cylindrical paste

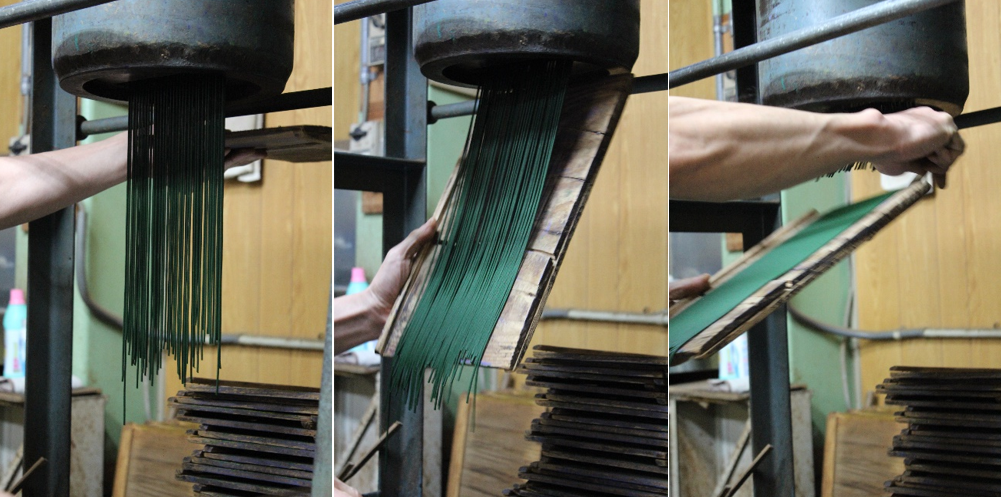

③ Push the paste through the extruder, capture the long strands on a board, then cut off the edges

④ Neatly place the strands on the drying board

⑤ Cut the incense sticks in proper lengths as required for different usage ⑥ Dry the incense

⑥ Dry the incense

⑦ Inspect the incense while bundling and packaging

⑦ Inspect the incense while bundling and packaging Much of the processes have been mechanized and are no longer done by hand, but some processes still require the expertise of an experienced incense maker. The blending of the ingredients—which determines the fragrance of senko—is such a process. Each manufacturer uses its own formula that remains a trade secret passed down only to the heir. Fragrance is not only the product but also an art that is at the center of this proud profession.

Much of the processes have been mechanized and are no longer done by hand, but some processes still require the expertise of an experienced incense maker. The blending of the ingredients—which determines the fragrance of senko—is such a process. Each manufacturer uses its own formula that remains a trade secret passed down only to the heir. Fragrance is not only the product but also an art that is at the center of this proud profession.

In recent years, incense manufacturers have come together under the umbrella of the Sakai Incense Industry Cooperative and are exploring creative ways to promote incense through initiatives such as incense making workshops at schools and special sales of incense to ward off evil on Halloween.

An Excellent All-Purpose Material, Cotton

Around the same time the production of senko began in Sakai, cotton was being cultivated in the area that is now the southern part of Osaka Prefecture according to some records. Situated along the Ishizugawa River, Sakai commanded an ideal climate and perfect environmental conditions for making wazarashi bleached cotton and the city continued to flourish.

Cotton is a durable material that maintains comfortable dryness even during the hot, muggy summer because of its ability to absorb moisture. In cold winter, on the other hand, the high thermal insulation of this all-purpose material retains the body heat. Reinforced by the superiority of the material, demand for wazarashi grew and, out of the thriving industry of wazarashi came a new dyeing technique called chusen. Chusen, literally meaning “pouring dye,” is a method in which the dye is poured onto layered wazarashi in one pour. The new method of dyeing was established in Sakai during the Meiji Period (1868-1912 CE).

Craftsmanship in the Manual Process

Kitayama Senkojo (located in Tsukunocho, Nishi-ku, Sakai) is one of the dyehouses of Sakai. Here, the chusen dyeing process is divided into various steps, each of which is performed repeatedly by one or two artisans.

① Applying glue

The spatula is worn down over time to fit artisan’s grip. (left)

The part of the stencil where glue is applied is mesh, and the pigment seeps into the parts where there is no glue.

Ise-Katagami paper stencils used in dyeing are a traditional craft of Suzuka City, Mie Prefecture.

② Building boarders

Dotebiki is a step in which various sections of the print are separated to prevent the pigments from mixing. By applying glue around each motif and essentially creating a border, colors from each section are prevented from spilling into other sections.

④ Rinsing and drying

The final step involves rinsing with water to remove the glue, spin drying, and drying in the sun.

The long lengths of colorful fabric hanging and dancing in the wind are a sight to see.

Innovative designs that take advantage of the texture of chusen are gaining popularity in recent years and are used in interior decoration as tapestries, tablecloths, and such. “I’m pleased to see chusen used in different ways. But I want everyone to feel the distinct texture of wazarashi firsthand. The more you use wazarashi, the more the fabric becomes natural to the touch. It’s almost addictive,” says Kitayama san, the president of a dyehouse called Kitayama Senkojo. Kitayama is active in the area’s revitalization efforts and serves as the deputy director of an NPO called Sukiyanen Tsukuno no Kai, which essentially means the “society of those who love Tsukuno.”

Innovative designs that take advantage of the texture of chusen are gaining popularity in recent years and are used in interior decoration as tapestries, tablecloths, and such. “I’m pleased to see chusen used in different ways. But I want everyone to feel the distinct texture of wazarashi firsthand. The more you use wazarashi, the more the fabric becomes natural to the touch. It’s almost addictive,” says Kitayama san, the president of a dyehouse called Kitayama Senkojo. Kitayama is active in the area’s revitalization efforts and serves as the deputy director of an NPO called Sukiyanen Tsukuno no Kai, which essentially means the “society of those who love Tsukuno.”

The neighborhood of Tsukuno is depicted in a tenugui towel.

The neighborhood of Tsukuno is depicted in a tenugui towel.

A variety of goods that take advantage of the bright colors of chusen

A variety of goods that take advantage of the bright colors of chusen